| Fashions of the 1870s were elaborately made and richly trimmed; volumes of material were used with flounce over flounce and tunic over tunic. In spite of the abandonment of the mid-nineteenth century crinoline’s monstrous bell-shaped curves, the 1870s woman was still unable to reap the full benefit of her emancipation. She could not dispense with a redundancy in some part or other of her attire. In the early 1870s the skirt, its front almost straight, blossomed out behind into a mountainous mass of folds. It was lavishly decorated with horizontal panels, finished at the hem with vertical pleating and trimmed with several wide flounces of lace or tucked and ruched bands of its own material. |

|

| Gray figured silk three piece 1870s dress with brown and white woven flower sprays. There is a long sleeve bodice, an ribbon trimmed overskirt and a fully lined skirt. The bodice and sleeves are lined with ivory linen. The front bodice fastens with hooks and has six gray silk decorative buttons. The overskirt and bodice are trimmed with wide brown silk ribbon. |

| These backward-drawn draperies were accentuated by the little “coat-tail” effect of the bodice, or by sash ends, tied in large bows, which appeared to hold up a vast puff of drapery, or by frills or ruffles, across the back of the skirt. The polonaise itself emphasized this line, being drawn up in multitudinous rich folds, sometimes set off with a little bow at the back of the waist, of which the ends cascaded formally, down over the loopings beneath.

|

| 1875 FASHION PLATE

LEFT: The ball dress is composed of a trained skirt of white silk, covered entirely with plaited flounces of white gauze; a drapery of blue silk, placed en tablier, is trimmed round with wide blonde or point d’Alencon, the heading to which is a wreath of pink roses with foliage. The body, “Isabeau,” is laced up the back with flat basques rounded front and back, and raised slightly on the hips, trimmed all round with blonde or lace; a large bouquet is placed at the back on the basque, just above the lace, from which falls a long wreath of roses, reaching nearly to the bottom flounce. Low round body, trimmed with a berthe of lace or blonde, and a wreath of roses, with bouquet of the same in front and on the shoulders. Chemisette of plaited gauze, drawn with a fine silk cord. Necklace, three rows of pearls. Coiffure a I’antique with wreath of roses and trail. Half long gloves. “Louis XV” fan, and shoes of white silk with blonde bows and roses. RIGHT: Toilette of faille jonquille and blonde worked with white jet. The trained skirt is set in at the waist in four double plaits, very deep, forming a fan to the bottom of the skirt; two wide bows and square ends, simply crossed and edged with narrow blonde, placed just below the basque at the back. The front is plaited horizontally, trimmed up each side with a wide bouillonne of the silk edged with double plaitings of silk and blonde. The low round body is laced up the back, and pointed in front; the basque is plain and round at the back, and hangs in a long end on each side, edged round with wide blonde, an elegant wreath of mountain ash falling down the center. The body is trimmed round the top with a bouillonne of silk edged with blonde, a wreath of mountain ash with bouquets of the same on the shoulders and in front. Chemisette of plaited crape. Headdress, diadem of flowers with trail falling over the back hair. “Louis XV” shoes of satin, trimmed with blonde. White kid gloves fastened with eight buttons. |

| Silk, velvet, beads, and fur were used, including yards of flossy silk fringe. Buttons were fancy with a silk network over them. A great deal of piece-velvet of the same color as the dress was introduced; bands of velvet some half-yard deep were carried across the front breadths, confining the fullness at the back, where they terminated in bows and sash ends. |

|

| Victorian dress from “Embellishments: Constructing Victorian Detail”, a beautifully illustrated book that helps you see Victorian fashion in a whole new way. [Photograph: Brian Smestad] |

The skirts were inordinately long and were tied back tightly, giving the appearance of swathing the figure in front. The flounces on the skirt were generally wide at the back and gathered, being edged with narrow frills, plaited all one way and caught down only half the length. Puffings at the side were sometimes used, in addition to side trimmings. At times, the bodices had basques, and were generally made as sleeveless jackets of velvet or of the shade of the material intermixed with the rest of the costume. Sometimes they had revers, or pointed collars at the throat, made of plaited silk, or they were fastened down the front with bands and buttons crossing each other. Violin backs were also the fashion, that is, a piece in the V shape, differing from the rest, and introduced into the back. The sleeves were fit closely to the arm, with cuffs and buttons. Photograph of Mrs. Algernon Sartoris (Nellie Grant) taken between 1870 and 1880. [Library of Congress Number: LC-DIG-cwpbh-03723] |

|

| Victorian Cotton Dress, 1875–85. [Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Gift of Richard Martin, 1993. Accession Number: 1993.35.1a–c. Metropolitan Museum of Art – Gallery Images, www.metmuseum.org] |

1875 FASHION PLATE 1875 FASHION PLATE

LEFT: Toilette of grey silk. The skirt, slightly trained, is trimmed at the back with one wide crossway flounce, quite scanty, surmounted by three narrow bouillonnes. Rather more than half way up, between these and the waist are placed three more bouillonnes the same width, drawn just tight enough to form a slight pouff below the waist. High plain body, forme “Princesse” in front en tablier quite flat, trimmed at each side with beaded passementerie a shade or two darker than the silk. The body is made with revers, trimmed with passementerie, as is the back, round the arm-holes and collar. At the back of the waist, which is round, are placed two long loop bows of silk, with crossing of the same. The sleeves, which are plain, and fitting at the top, are trimmed with two wide frills of plaited silk falling over the hand, with a heading of passementerie. Undersleeves and frill of plaited muslin. Black felt hat, trimmed with a dahlia in front and long grey feather. RIGHT: Costume of velvet and silk, for slight mourning. Dress of black silk, slightly trained, trimmed with a wide plaited flounce, surmounted by three narrow bouillonnes. A little above is a second flounce, also plaited, but not more than half the width, with three narrow bouillonnes. The “Princesse” body has a short rounded basque at the back, open with revers in front, fastened with buttons to the bottom of the tablier, which reaches to the top of the lower flounce. The tablier is trimmed with two narrow plaited flounces of faille, the same trimming carried round the basque, which is held up by a sash of velvet made with two very long hanging bows and two wide ends cut crossway at the ends, but perfectly plain. A frill of plaited silk round the opening of the body, with one of muslin under. The sleeves, which, like the body and tablier, are of black velvet, are plain and nearly tight; they are trimmed from the wrist with four narrow bouillonnes of silk, and a rosette of the same at the wrist and elbow. Undersleeve of plaited muslin. “Marie Stuart” toque of black velvet trimmed with a bouillonne of faille and jet fringe; long veil of crepe lisse. |

The robe a la polonaise had almost an eighteenth-century flavor, its closely fitted bodice and looped-up skirt (frequently held by large bows of rich ribbon with hanging ends) over a contrasting underskirt giving an effect not unlike the pannier dresses of the eighteenth century. The use of broad and handsome ribbons, in profusion, was very customary at this time; and narrower ribbons, pleated or ruched, tied with fringe, innumerable small buttons, and elaborate braiding in the trimming of all garments. It fell to the beautiful Alexandra, Princess of Wales, to inaugurate the next marked change in the mode. The robe a la Princesse, with its slim waist at the natural level and slender flowing lines, may be attributed directly to her taste. The suavity and grace of this new mode, as contrasted with the extravagances of the crinoline, maintained their influence for many years, although by the early eighties bustles had returned to mar the earlier simplicity. The Princess robe, strictly speaking, was cut without any seam at the waist, and molded the figure from neck to hip, where it flowed on in sweeping draperies; but the influence of this style was so strong that even when a dress was made with a separate bodice and skirt the line remained essentially the same, with its smoothly fitted sweep from shoulder to hip, no matter how elaborate the drapings of the skirt might be. From 1875 onwards this feeling is strongly stressed. Photograph of Mrs. Algernon Sartoris (Nellie Grant) taken between 1870 and 1880. [Library of Congress Number: LC-DIG-cwpbh-03778] |

1876 FASHION PLATE 1876 FASHION PLATE

LEFT: Toilette de chateau, composed of rose-colored poult de soie, and a very pale salmon figured cashmere. The skirt is of silk and trimmed round with a plaited flounce, gradually increasing in width at the back breadths. “Princesse” polonaise of cashmere, very long, and trimmed round the bottom with a fancy galon and ball fringe. The polonaise is made to fit by seams, and is buttoned down the front. The upper part of the side breadths is gathered under the back, so as to slightly drape. The back breadths are fastened at the waist, and hang down between, and are trimmed with galon. This galon meets at the waist, and is carried over the shoulders en bretelles, and down the front with a pink silk revers. The sleeves are open at the back, trimmed round with galon over a pink silk cuff, which is laid on in plaits behind, showing through the opening, at the bottom of which they are held together by a narrow bias band. “Watteau” bonnet of pink silk, the crown nearly covered with feathers; the brim trimmed underneath with lace and hortensia. Cream-colored lace is put full across the back, and forms strings, which cross in front. RIGHT: Costume of faille and crepon de Chine, of a mauve color, trimmed with velvet of a deeper shade. The skirt is of silk, and has a flounce made in plaits, caught two together by a kind of small puff nearly in the center. The width of the flounce is increased towards the back. Tablier draped in plaits at the sides, and trimmed down the front with three velvet bows. Two pointed ends, trimmed round with velvet, matching the tablier, are formed into long bows and ends at the back. Long wide velvet bows and ends at the side. Corsage buttoned in front, made with a plain basque, simply trimmed with two rows of bias velvet, and with two bows in front. Tight sleeve, ending in a wide double cuff, with a band of velvet fastened under a bow at the back. Capote of China crape, trimmed with velvet and feathers, and a bird placed on one side. A plaiting of crepe lisse is placed round under the brim. |

This is featured post 1 title

To set your featured posts, please go to your theme options page in wp-admin. You can also disable featured posts slideshow if you don't wish to display them.

This is featured post 2 title

To set your featured posts, please go to your theme options page in wp-admin. You can also disable featured posts slideshow if you don't wish to display them.

This is featured post 3 title

To set your featured posts, please go to your theme options page in wp-admin. You can also disable featured posts slideshow if you don't wish to display them.

1870s Victorian Fashion

四月 4th, 2016

四月 4th, 2016  ok

ok The Crinoline or Hoop Skirt

四月 3rd, 2016

四月 3rd, 2016  ok

ok |

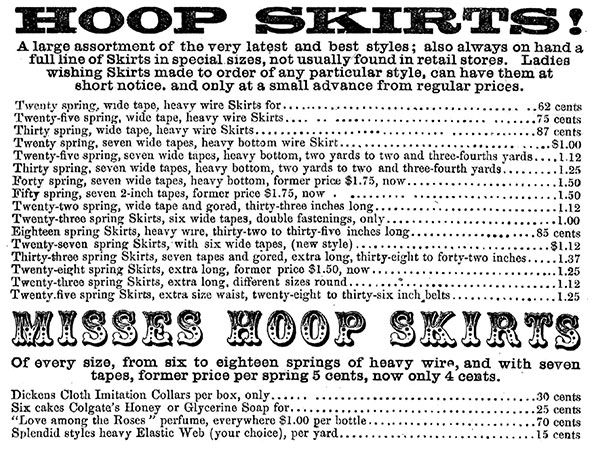

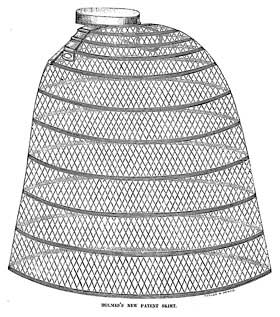

The 1800s crinoline, also called a hoop skirt or extension skirt, was inspired by the open cage or frame style of the 16th and 17th century farthingale and the 18th century pannier. The Victorian crinoline developed various appearances over it’s fashion lifetime as a result of new designs and methods of manufacture. |

|

The word crinoline originally referred to a stiff fabric with a weft of horse hair and a warp of cotton or linen thread (the Latin crinis meaning hair and linum meaning flax). This fabric made its first appearance in fashion in the 1830s when it was used in women’s petticoats to support and shape the growing length and diameter of the early Victorian dress. Often a petticoat of this stiffened fabric was worn with up to six starched petticoats in an attempt to achieve the big skirt effect; these tangling petticoats were heavy, bulky and generally uncomfortable. The word crinoline originally referred to a stiff fabric with a weft of horse hair and a warp of cotton or linen thread (the Latin crinis meaning hair and linum meaning flax). This fabric made its first appearance in fashion in the 1830s when it was used in women’s petticoats to support and shape the growing length and diameter of the early Victorian dress. Often a petticoat of this stiffened fabric was worn with up to six starched petticoats in an attempt to achieve the big skirt effect; these tangling petticoats were heavy, bulky and generally uncomfortable. |

|

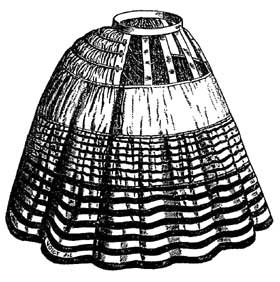

| The heavy folds of velvet fabric of this Victorian ball gown are supported by a hoop skirt. At its peak in size, the crinoline reached a diameter of up to 180 centimeters, almost six feet. |

Next rings of stiffened cord encircling the petticoat were tried. These corded skirts were too heavy, thus unable to support their own weight. During the 1850s the extension skirt was developed with rigidity added to the skirt in the form of cane and whalebone hoops. These hoops created the desired width but were too easily broken. Subsequently thin strips of brass replaced the cane but the brass did not possess sufficient elasticity to enable the skirt to resume its rounded form after being submitted to considerable pressure. Next rings of stiffened cord encircling the petticoat were tried. These corded skirts were too heavy, thus unable to support their own weight. During the 1850s the extension skirt was developed with rigidity added to the skirt in the form of cane and whalebone hoops. These hoops created the desired width but were too easily broken. Subsequently thin strips of brass replaced the cane but the brass did not possess sufficient elasticity to enable the skirt to resume its rounded form after being submitted to considerable pressure.

Ultimately hoops of flattened steel wire were employed to stiffen the “extension skirts” of the late 1850s and were found to be lighter than |

|

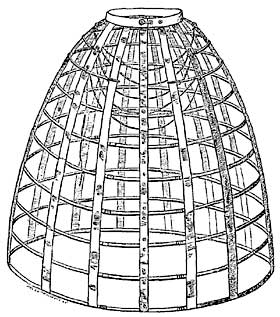

| MID-19th CENTURY CRINOLINE OR HOOP SKIRT [Photo Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Gallery Collection |

|

| MID-19th CENTURY CAGE CRINOLINE OR HOOP SKIRT [Photo Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Gallery Collection, |

The best steel for making the wire for the crinoline cage came from England, in the form of coiled rods, of about ¾ of an inch in thickness. The first operation to which it was submitted, was heating it to about a bright red heat in a furnace  adapted for the purpose, by which it was softened. It was next scoured with acid, to remove all oxide from its surface, after which it was coated with rye flour and dried in a special apparatus. Next the steel rod was reduced in diameter, while at the same time greatly extending its length until it became a No. 19 wire in size, and had been extended in length from a few yards to no less than two thousand yards. After having been reduced to the requisite size it was flattened by drawing it from one reel and winding it upon another, then hardened and tempered. Lastly yarn was braided around the wire, and then sent to the warehouse to be placed in skirts. No less than 60,000 yards of flattened steel wire were made and covered daily in this operation. These covered wire hoops were suspended by tapes in the form of a skirt, descending in increasing diameters from a band worn around the woman’s waist. adapted for the purpose, by which it was softened. It was next scoured with acid, to remove all oxide from its surface, after which it was coated with rye flour and dried in a special apparatus. Next the steel rod was reduced in diameter, while at the same time greatly extending its length until it became a No. 19 wire in size, and had been extended in length from a few yards to no less than two thousand yards. After having been reduced to the requisite size it was flattened by drawing it from one reel and winding it upon another, then hardened and tempered. Lastly yarn was braided around the wire, and then sent to the warehouse to be placed in skirts. No less than 60,000 yards of flattened steel wire were made and covered daily in this operation. These covered wire hoops were suspended by tapes in the form of a skirt, descending in increasing diameters from a band worn around the woman’s waist. |

|

|

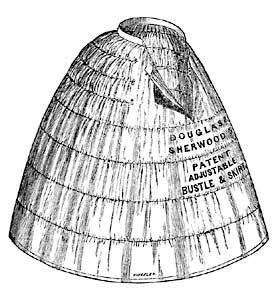

| DOUGLAS & SHERWOOD’S PATENT ADJUSTABLE BUSTLE AND SKIRT – 1858

They are made of fine cloth. The Bustle is of fine whalebone, extending part of the way round the skirt; at their ends are eyelets, through which a corset lace is passed. GODEY’S LADY’S BOOK, 1858 |

| In 1858, Douglas & Sherwood referred to themselves as a “manufactory of hooped skirts” with almost four hundred young women employed in their factory. They advertised their new style, the “Adjustable Bustle and Skirt” in the February 1858 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine; the bustle was made with “round whalebone.” Later that year, Douglas & Sherwood introduced their “Balmoral Skirt” which combined both the hoop and a woolen, red and black graduated stripe skirt. |

|

| MID-19th CENTURY CRINOLINE OR HOOP SKIRT [Photo Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Gallery Collection |

|

| DOUGLAS & SHERWOOD’S NEW EXPANSION SKIRT (HOOP SKIRT)- 1858 |

|

| DOUGLAS & SHERWOOD’S PATENT BALMORAL HOOP SKIRT – 1858 |

|

| The “Highland” costume was featured in Peterson’s Magazine in 1861. With this dress, a Balmoral hoop skirt was indispensable. Some ladies made the petticoat of plain gray flannel, and ornamented it with rows of red cloth or flannel. |

| In 1859, Osborn & Vincent of New York listed itself as the owners of the extension skirt patent. Their most popular skirts in 1859 were the “Imperial Skirt” and their new “Champion Belle.” The latter extension skirt was described as “exceedingly light and graceful,” as well as “extremely flexible and convenient in carriages, cars, and stages.” In an advertisement, Osborn & Vincent listed the many manufacturers and dealers of the extension skirt using their patent: |

Douglas & Sherwood, W.S. & C.H. Thomson, J. Wilcox & Co., Wallace & Sons, Arms Brothers, J.P. Moran & Co., C. L. Harding, S. H. Doughty, Chas. A. Postley, R. France, Theodore Schmidt, Ernest L. Schmidt, H. S. Hewson, Chas. P. Colt, John Holmes, J. & W. Beck, H. G. McKenna, Frost & Co., G. M. Jacobs & Co., Jos. B. Wesley, Moritz Cohen, Emanuel Mandel, Stein & Stern, David Henius, Fisher & Herman, Union Skirt Company. Douglas & Sherwood, W.S. & C.H. Thomson, J. Wilcox & Co., Wallace & Sons, Arms Brothers, J.P. Moran & Co., C. L. Harding, S. H. Doughty, Chas. A. Postley, R. France, Theodore Schmidt, Ernest L. Schmidt, H. S. Hewson, Chas. P. Colt, John Holmes, J. & W. Beck, H. G. McKenna, Frost & Co., G. M. Jacobs & Co., Jos. B. Wesley, Moritz Cohen, Emanuel Mandel, Stein & Stern, David Henius, Fisher & Herman, Union Skirt Company. |

|

Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine in 1859 provided a picture of “The Woven Extension Skirt” saying that it was impossible to rip or tear the tapes “as they were wove in the springs.” Also in 1859, J. Holmes & Co. stated that in spite of its lightness and compactness, an extension skirt’s primary concern was “easy adjustability into smaller space for the parlor or expansion into ample dimension for the promenade.” J. Holmes & Co. introduced their new patent extension skirt with a system of clasps and slides; this skirt had a watch spring bustle wrought into the skirt, forming a uniform bishop shape throwing the fullness at the back, and hanging gracefully straight in the front. Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine in 1859 provided a picture of “The Woven Extension Skirt” saying that it was impossible to rip or tear the tapes “as they were wove in the springs.” Also in 1859, J. Holmes & Co. stated that in spite of its lightness and compactness, an extension skirt’s primary concern was “easy adjustability into smaller space for the parlor or expansion into ample dimension for the promenade.” J. Holmes & Co. introduced their new patent extension skirt with a system of clasps and slides; this skirt had a watch spring bustle wrought into the skirt, forming a uniform bishop shape throwing the fullness at the back, and hanging gracefully straight in the front. |

|

| The crinoline reached its maximum dimensions by 1860 but then gradually began to change. An 1860 ladies’ magazine referred to the crinoline as “bird cagey contrivances.” |

The crinoline reached its maximum dimensions by 1860 but then gradually began to change. An 1860 ladies’ magazine referred to the crinoline as “bird cagey contrivances” and stated, “The pyramidal crinoline, diminished in size but in demi-train, is in favor.” In 1862, the English Woman’s Domestic Magazine recommended the W.S. Thomson crinoline to “those ladies who prefer the open petticoats, or cages.” Over 2,000 workers were employed in Thomson’s London location, producing 4,000 crinoline cages a day. According to the magazine, Thomson’s crinolines possessed two advantages over other manufactured skirts: “the binding on which the steels are threaded cannot break in consequence of it being so broad; and the eyelet-holes do not wear away the tape so quickly as do the metal claws usually used to secure the steels in their places.” Furthermore, the back of the jupon of the Thomson crinoline was threaded in the shape of a gore, to suit the fashionable train skirts. The upper half of the back part of the crinoline was made with a small inside one which passed half way round; but being smaller than the outside, threw the skirt off behind in a demi-train. The crinoline reached its maximum dimensions by 1860 but then gradually began to change. An 1860 ladies’ magazine referred to the crinoline as “bird cagey contrivances” and stated, “The pyramidal crinoline, diminished in size but in demi-train, is in favor.” In 1862, the English Woman’s Domestic Magazine recommended the W.S. Thomson crinoline to “those ladies who prefer the open petticoats, or cages.” Over 2,000 workers were employed in Thomson’s London location, producing 4,000 crinoline cages a day. According to the magazine, Thomson’s crinolines possessed two advantages over other manufactured skirts: “the binding on which the steels are threaded cannot break in consequence of it being so broad; and the eyelet-holes do not wear away the tape so quickly as do the metal claws usually used to secure the steels in their places.” Furthermore, the back of the jupon of the Thomson crinoline was threaded in the shape of a gore, to suit the fashionable train skirts. The upper half of the back part of the crinoline was made with a small inside one which passed half way round; but being smaller than the outside, threw the skirt off behind in a demi-train. |

|

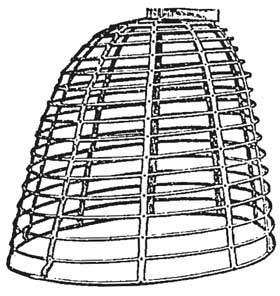

| By them middle of the 1860s, the dome-like shape of a women’s skirt decreased with the volume disappearing in the front and gathering at the back. In 1865, A.T. Stewart advertised a “Bon-Ton Skirt,” a wire flexible spring skirt that kept the front of the skirt “fitting closely to the form.” By 1867, Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine decided that “ladies enjoyed more advantages respecting dress – close and flowing sleeves, short and long skirts, tight-fitting, case like dresses, others with plaits at the back . . . waists fitting corset-like over the hips, hoops clinging to the figure, and the positive extreme bustles!” The pannier fullness at the back was made to curve gracefully with the front of the skirt perfectly straight, fitting smoothly over the figure. |

THOMSON’S CRINOLINE, Label reads: Prize Medal Skirt. By Her Majesty’s Royal Patent Registered Trade Mark 20 the royal coat of arms and a crown printed on the herringbone woven tape waistband, vertical herringbone woven tapes 1 inch; 2.5 cm wide, fastened to the hoops with brass eyelets, the front two crossing, nineteen cotton covered steel adjustable hoops, height 32 inches; 82 cm; diameter approximately 2 feet; 60 cm. Available for purchase from Meg Andrews at www.meg-andrews.com. |

|

|

| In 1868, a Boston Massachusetts’ store advertised latest styles of “wire skirts.” Prices of the hoop skirts varied according to the number of springs, which ranged from 18 to 50 springs. |

|

| In 1868, Harper’s Bazaar spoke of the new “Winged Lace” skirt in which the upper part of the under-skirt was laced together, then came a few hoops, and below there was the open winged front. This style prevented the feet from becoming entangled in the skirt. The skirt measured 85 inches in circumference; could be put in the tub and washed thoroughly; with a retail price of $3.00. Lastly in 1868, Arthur’s Home Magazine reported, “The fickle goddess appears to have decreed as follows . . . there shall be abundance of crinoline, or bustle, or panier, or tournure (for the bunch at the back goes by a variety of names), just below the waist, but that there should be little on none at the lower half of the skirt.” |

The Archduchess Marie Antoinette

四月 2nd, 2016

四月 2nd, 2016  ok

ok Emperor Francis and Empress Maria Theresa of Austria Ruled over a large area of central Europe . Maria Theresa, who had inherited the throne from her father, was a strong and determined woman. On the night of November 2.1755, she took a break from her reports and other government paperwork when her labor pains grew too strong. In the evening ,she gave birth to Maria Antonia Josepha Joanna . Emperor Francis Announced the Arrival of his daughter to the members of his royal cour gathered at their palace in Vienna.

Maria Antonia joined a household already full of archdukes and archduchesses —-four brothers and seven sisters. Another brother would be born the following year! It was royal tradition to give all the archduchesses the first name “Maria”. The girls were called by their second names, so Maria Antonia’s parents called her Antonia.

The family spent winters at their place in the heart of the city.In the spring and summer, however, they moved to another enormous palace about five miles away.Decorated with mirrors, painted ceilings and tapestries on the walls, this palace had many rooms for each child .It was surrounded by the gardens and woods of a five-hundred-acre park. There was even a zoo with a camel puma, and rhinoceros.

Even thouth Austria had an emperor and an empress Maria Theresa was the ruler. Her husband , Francis, simply assisted her. Empress Maria Theresa was much too buys to watch her children. so she hired governesses to take care of them and tutors to teach them. As royalty the archdukes and archduchesses lived a glamorous life. For fun ,they spent hours riding horses and hunting. During the cold Austrian winters ,they rode swan-shaped sleds through the snow.

Antonia spent more time playing on the place grounds than paying attention to her lesson. She had a beautiful voice and performed in family concerts, singing while her brothers and sisters played the music.

In 1762, when antonia was six years old, a special musician visited the royal family in Vienna. His name was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart . Mozart was the same age as Antonia. Stories say that the little musician lipped on the well-polished floor of the palace. When Antonia helped him up, Mozart declared that he wanted to marry her.

Antoia’s father, the emperor, died in August 1765.Antonia was only nine years old. The empress, now ruling with her oldest son, Joseph, had a new focus. She was determined to arrange good marriages for her daughters.At the time , royal marriages were very important. Royal couples did not marry each other for love.They married to strengthen the bond between two countries so that the countries would support each other, especially during times of war. Maria Theresa especially wanted to marry one of her daughters to Louis Augueste, the future king of France.

Austria And France had a history of conflict. More recently , however , the two countries were at peace. Maria Theresa Thought a marriage between her own family — the Habsburgs–and the French Bourbon family would strengthen the ties between them. Antonia was the best choice for marriage. She was closest in age to the dauphin.

The French agreed to the marriage, so the empress began to prepare ther daughter. She hired a ballet teacher to help Antonia move more gracefully. A Frenchman straightened Antonia’s crooked teeth with wires. A hairdresser from Paris styled her hair in the most modern ways.

France also sent a tutor, Abbe de Vermond , to the imperial palace in 1768. When Vermond met Antonia he observed,” She has most graceful figure; holds herself well; and if .. she grows a little taller. she will possess every good quality one could wish for in a great priness.”

The thirteen-year-old archduchess was certainly charming , with her blue eyes, blond hair, and pink-and-white skin. Yet Vermond soon discovered that she knew very little. Her tutors had let her do whatever she wanted. So Vermond now made Antonia study religion.French literature, French history, and the French language.

Antonia was growing into a fine young lady, worthy to be the new French princess.

Who was Marie Antoinette

四月 1st, 2016

四月 1st, 2016  ok

ok On April 21, 1770, fifteen-year-old Marie Antoinette left home and traveled to France. She had always lived a royal life . Her prents were the emperor and empress of Austria.The young archduchess was leaving behind her beloved homeland. She was engaged to marry Louis Auguste,the future king of France.

Marie Antoinette rode in a jeweled coach amid a parade of more than fifty other carriages. Hairdressers, chefs, and other attendants traveled with her for the two-and-a-half-week journey.Peasants cheered along the road between Vienna, Austria , and Strasbourg ,France.They hoped to catch a glimpse of the young bride-to-be.

The royal procession reached the Rhine River, where a new building stood on an island. Marie Antoinette said good-bye to the Austrian people who had traveled with her.When she entered the building,she had to take off all of her Austrian clothes.She was given a French Gown made of golden Fabric.She wasn’t allowed to bring anything from Austria into France,not even Mops, Her little pug dog.

In an official ceremony ,she was handed over to the French. When she opened the doors on the side of the building that face France, crowds of noblemen and noblewomen greeted her. Marie Antoinette cried , but she tried to be brave.The whole city of Strasbourg held a holiday in Marie Antoinette’s honor. A French procession of carriages then carried the to her new busband and her new life at the grand palace of Versailles (ver-SIGH).

Marie Antoinette Became the queen of France while still only a teenager.She had no idea how to be a good leader. Many people in france were poor. They had to pay high taxes. Their Taxes went to the royal family. Some of the money was spent running the government.But plenty was also spent on gowns, jewels , parties, and fancy palaces. The common people became angry with their king and queen for wasting money while they had so little. By the end of Marie Antoinette’s life. the French people were cheering for her death.

More fancy Marie Antoinette Dresses in the wholesalelolita.com

Civil War Quilts

四月 1st, 2016

四月 1st, 2016  ok

ok Civil War quilts played important roles in both the North and South.They were used in the hospital, on the battlefield, and on the home front, but an important question remains:

Were they actually used as flags on the Underground Railroad?

Quilt Patterns and Materials

When examining vintage quilts, it is important to remember that the ones that survive were special and generally do not represent daily life.

Autograph quilts were a popular memento, so many of those survive, but utility quilts had simple designs.

Old dresses and other articles of clothing were recycled into Civil War quilts so that nothing went to waste.

If you are planning to make reproduction Victorian quilts, keep in mind that Turkey red and Prussian blue were commonly available dyes. The only shades of purple available were pale and brownish.

Also, Victorian women were proud of their new and expensive sewing machines, so they did not try to hide machine stitches!

The Underground Railroad

The metaphoric Underground Railroad was a widespread system of safe houses where fugitive slaves could hide while traveling north.

There is a popular belief that quilts were used to signal hidden messages, but no first-hand African-American accounts mention quilts.

There is also a mistaken belief that the log cabin quilt pattern was used as a signal, but it was most popular between 1870 and 1920, after the Civil War. The earliest reference to such as pattern is in connection with Union fundraisers in 1863 when the Underground Railroad escape routes were no longer operating. My source for these facts is Quilts from the Civil War by Barbara Brackman.

It is more accurate to view the log cabin quilt pattern as a sign of allegiance to President Abraham Lincoln, who was born in a log cabin. This design became a memorial to the assassinated president, so that is why it was not made in former Confederate states. They did not care to mourn the president whose election caused war to start.

Quilt Use and Abuse

Quilting therapy and knitting socks helped the women left at home to deal with the difficult times. It was something useful and expressive to work on while the loved ones were away.

While some quilts were made with the hope of nursing the sick and wounded, other quilts were stitched to auction off as fundraisers for women’s groups raising money in support of the war.

Many quilts were also used to wrap family treasures hidden inside chests or attics or more unusual places like caves, wells, or buried under logs. Some developed stains from the harsh storage. Others were used by soldiers as a poncho or wrap, or torn up and used for bandages.

Unfortunately, quilts could spread diseases like typhus, so even those that were not torn up may have been destroyed for sanitation purposes.

Southern Quilts

There were no Confederate printed calico designs because all of the calico factories were located in the North. Since the cotton factories were in the North and imported cloth could not pass through the blockaded ports, many Southern women had to resort to making their own homespun fabric, as the slaves did. There was such as shortage of fabric that carpets were cut up and turned into bedding!

The Gunboat Fairs were held to raise money for the Confederate Navy. The iron-clad Merrimack inspired an interest in developing submarine technology.

Northern Quilts

In the North, fancy quilts were auctioned off as a fundraiser at anti-slavery fairs. There were many patriotic Civil War quilt patterns to celebrate the Union. Sewing circles and public groups were already a custom, so they adapted to making supplies for soldiers. USSC donations were stamped with a mark to prevent theft.

Civil War Womens Clothing

三月 31st, 2016

三月 31st, 2016  ok

ok The Civil War womens clothing outfits worn by the female citizens of Gettysburg and Victorian women visiting after the battle are hard for us to imagine in the modern age of shorts and tank tops.There were specialized Civil War dresses every occasion: mourning gowns, ball gowns, riding habits, etc.

The Hoop Skirt

Civil War Southern belles are best known for their hoops. Civil War ladies clothing and fashion in the 1860s featured the hoop skirt at its greatest width. The hoop extended slightly father out in the back than in the front.

It took up to 5 yards of fabric to make a Victorian hoop skirt.

The cloth supply to the South from northern mills was cut off during the war, so some women made smaller skirts to save material and help the war effort. Or perhaps they recycled curtains as in Gone with the Wind!

Practical Civil War Dresses

While a hoop skirt is a good outfit for Gettysburg Remembrance Day on November 19th when ladies would have dressed up to hear Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, it is likely not what most citizens were wearing during the battle or while helping in hospitals.

Wealthy Victorian women wore several dresses each day. A “morning dress” was plainer. An “evening dress” was low on the shoulders, and suitable for a party. A “walking dress” had a longer peltote (a type of jacket essential to the outfit) over it that matched the skirt.

On the other hand, working class women during the Civil War likely only had two or three everyday dresses, one Sunday best outfit, and maybe the newest everyday dress reserved for going to town or visiting people.

Layers of Civil War Womens Clothing

Here’s a list of the Civil War womens clothing that they wore starting next to the skin and working out in layers:

Layer 1

* Drawers (underpants) made of cotton or linen and trimmed with lace

* Chemise (long undershirt) usually made of linen

* Stockings held up with garters

Layer 2

* Corset or stays stiffened with whale bone

* Crinoline, hoop skirt, or 1 or 2 petticoats (dark color if traveling due to mud and dirt)

Layer 3

* Petticoat bodice, corset cover, or camisole

Layer 4

* Bodice

* Skirt, often held up with “braces” (suspenders)

* Belt

* Slippers made of satin, velvet, done in knit, or crochet

Layer 5 (outerwear for leaving the house)

* Shawl, jacket, or mantle

* Gloves or mitts

* Button up boots

* Parasol

* Bonnet or hat

* Bag or purse

* Handkerchief

* Fan sometimes made of sandalwood

* Watch pocket

A fine lady never painted her face (wore make up). Sometimes she did carry smelling salts incase she fainted. For festive occasions, young ladies wore a nosegay of flowers.

Visit the Smithsonian website to see a vintage photo of a lady in Civil War womens clothing. (Opens in a new window.) There is also a color fashion plate from Godey’s Ladies Book, June 1862. It was a magazine that served the upper middle class, but those of lower status would certainly have been influenced by the Civil War ladies clothing fashions of high society and tried to imitate them.

I have collected some photos of Civil War dresses from the archives of the Library of Congress.

Color Choices

According to magazine articles from the era, a lady should choose colors based on harmony, simplicity, and influenced by nature.

We might consider some of their flower inspired color combinations gaudy now; however, they were afraid of being gaudy and looking like they were wearing Joseph’s coat from the Biblical story, so they stuck to two main colors in most ensembles.

Various styles of trim and braid were popular. Accessories for Civil War womens clothing were often covered in embroidery, as the vintage patterns from Godey’s Ladies Book and Peterson’s Magazine testify.

More about Women’s Gloves

Victorian modesty dictated that ladies should wear gloves when going out. She must have nice clean gloves on for church or dancing. They were not worn at all times and removed for eating. Think of them as part of Civil War womens clothing outerwear or things put on when going visiting such as the shawl, cape, and bonnet.

Crochet mitts were popular in the 1840s, so wearing them to an 1863 event is out of fashion. Perhaps someone old and clinging to her younger days would wear them, but white kid gloves extending to cover the wrist were the most popular and fashionable gloves.

If you crochet or knit and want to make something for your ensemble, why not make a snood? It was a lacy type of hairnet used to cover a bun.

Is there a hair in your necklace?

Hair jewelry was a special type of Civil War jewelry used to remember loved ones separated by distance or death. It included the person’s hair in rings, brooches, bracelets, necklaces, earrings, or even watch chains.

This accessory in Civil War womens clothing was a type of sentimental jewelry first given as a token of friendship or love, but as the Victorian era progressed, it became mourning jewelry.

Victorians had an obsession about hair being covered or worn up, and they were very careful about touching each other, hence the gloves. In this form, hair jewelry allowed men and women to touch an intimate part of each other.

The hair could be clipped from the head, but many ladies had a hair receiver on their dresser and emptied their brush into it.

About Marie Antoinette

三月 30th, 2016

三月 30th, 2016  ok

ok Born in Vienna, Austria, in 1755, Marie Antoinette married the future French king Louis XVI when she was just 15 years old. The young couple soon came to symbolize all of the excesses of the reviled French monarchy, and Marie Antoinette herself became the target of a great deal of vicious gossip. After the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, the royal family was forced to live under the supervision of revolutionary authorities. In 1793, the king was executed; then, Marie Antoinette was arrested and tried for trumped-up crimes against the French republic. She was convicted and sent to the guillotine on October 16, 1793.

Marie Antoinette: Early Life

Marie Antoinette, the 15th child of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I and the powerful Habsburg empress Maria Theresa, was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1755–an age of great instability for European monarchies. In 1766, as a way to cement the relatively new alliance between the French and Habsburg thrones, Maria Theresa promised her young daughter’s hand in marriage to the future king Louis XVI of France. Four years later, Marie Antoinette and the dauphin were married by proxy in Vienna. (They were 15 and 16 years old, and they had never met.) On May 16, 1770, a lavish second wedding ceremony took place in the royal chapel at Versailles. More than 5,000 guests watched as the two teenagers were married. It was the beginning of Marie Antoinette’s life in the public eye.

Marie Antoinette: Life at Versailles

Life as a public figure was not easy for Marie Antoinette. Her marriage was difficult and, as she had very few official duties, she spent most of her time socializing and indulging her extravagant tastes. (For example, she had a model farm built on the palace grounds so that she and her ladies-in-waiting could dress in elaborate costumes and pretend to be milkmaids and shepherdesses.) Widely circulated newspapers and inexpensive pamphlets poked fun at the queen’s profligate behavior and spread outlandish, even pornographic rumors about her. Before long, it had become fashionable to blame Marie Antoinette for all of France’s problems.

Marie Antoinette: The French Revolution

In fact, the nation’s difficulties were not the young queen’s fault. Eighteenth-century colonial wars–particularly the American Revolution, in which the French had intervened on behalf of the colonists–had created a tremendous debt for the French state. The people who owned most of the property in France, such as the Catholic Church (the “First Estate”) and the nobility (the “Second Estate”), generally did not have to pay taxes on their wealth; ordinary people, on the other hand, felt squeezed by high taxes and resentful of the royal family’s conspicuous spending.

Louis XVI and his advisers tried to impose a more representative system of taxation, but the nobility resisted. (The popular press blamed Marie Antoinette for this–she was known as “Madame Veto,” among other things–though she was far from the only wealthy person in France to defend the privileges of the aristocracy.) In 1789, representatives from all three estates (the clergy, the nobility and the common people) met at Versailles to come up with a plan for the reform of the French state, but noblemen and clergymen were still reluctant to give up their prerogatives. The “Third Estate” delegates, inspired by Enlightenment ideas about personal liberty and civic equality, formed a “National Assembly” that placed government in the hands of French citizens for the first time.

At the same time, conditions worsened for ordinary French people, and many became convinced that the monarchy and the nobility were conspiring against them. Marie Antoinette continued to be a convenient target for their rage. Cartoonists and pamphleteers depicted her as an “Austrian whore” doing everything she could to undermine the French nation. In October 1789, a mob of Parisian women protesting the high cost of bread and other goods marched to Versailles, dragged the entire royal family back to the city, and imprisoned them in the Tuileries.

In June 1791, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette fled Paris and headed for the Austrian border–where, rumor had it, the queen’s brother, the Holy Roman Emperor, waited with troops ready to invade France, overthrow the revolutionary government and restore the power of the monarchy and the nobility. This incident, it seemed to many, was proof that the queen was not just a foreigner: She was a traitor.

Marie Antoinette: The Terror

The royal family was returned to Paris and Louis XVI was restored to the throne. However, many revolutionaries began to argue that the most insidious enemies of the state were not the nobles but the monarchs themselves. In April 1792, partly as a way to test the loyalties of the king and queen, the Jacobin (radical revolutionary) government declared war on Austria. The French army was in a shambles and the war did not go well—a turn of events that many blamed on the foreign-born queen. In August, another mob stormed the Tuileries, overthrew the monarchy and locked the family in a tower. In September, revolutionaries began to massacre royalist prisoners by the thousands. One of Marie Antoinette’s best friends, the Princesse de Lamballe, was dismembered in the street, and revolutionaries paraded her head and body parts through Paris. In December, Louis XVI was put on trial for treason; in January, he was executed.

The campaign against Marie Antoinette likewise grew stronger. In July 1793, she lost custody of her young son, who was forced to accuse her of sexual abuse and incest before a Revolutionary tribunal. In October, she was convicted of treason and sent to the guillotine. She was 37 years old.

Marie Antoinette: Legacy

The story of revolution and resistance in 18th-century France is a complicated one, and no two historians tell the story the same way. However, it is clear that for the revolutionaries, Marie Antoinette’s significance was mainly, powerfully symbolic. She and the people around her seemed to represent everything that was wrong with the monarchy and the Second Estate: They appeared to be tone-deaf, out of touch, disloyal (along with her allegedly treasonous behavior, writers and pamphleteers frequently accused the queen of adultery) and self-interested. What Marie Antoinette was actually like was beside the point; the image of the queen was far more influential than the woman herself.

Bustle Dresses/Skirts

三月 29th, 2016

三月 29th, 2016  ok

ok There were three distinct fashion trends during the Victorian era, and all are considered “Bustle Dresses”. These were the Early Bustle period (1869-1876), the Natural Form period (1877-1882), and the Late Bustle period (1883-1889). The combination of a tight bodice and a very full skirt with bustle and drapery was thought to enhance the look of a tiny waist. A 15-inch waist was considered ideal, and fashion plates of the day always illustrated women with impossibly small “wasp waists”.

The Early Bustle period (1869-1876) is characterized by tight-fitting bodices, which were worn with separate skirts. The bodice usually had a very high neck, and long closely-fitted sleeves. The sleeve was “dropped” from the shoulder a bit more than we are used to seeing today, and there was very little fullness at the sleeve head. A bustle was worn under the skirt, as well as two or more petticoats. There was usually an overskirt as well, either in the form of an apron-like drape across the front of the skirt, and/or an elaborately draped and pleated overskirt which covered the back of the skirt. The skirt itself was usually embellished with layers of ruffles, rouching or other trims.

The Natural Form period (1877-1882) dispensed with the bustle entirely. However, elaborate draping and pleating at the rear of the skirts still kept some of the bustle silhouette intact. Skirts during the natural form period were flatter in the front, and fullness was carried toward the back of the skirt. The “cuirasse bodice” which was based on a military style, dipped below the waistline at the front and back of the bodice, and was cut higher over the hips. Overskirts were still popular, but the fullness of the skirt was often drawn toward the back of the skirt using hidden tapes, which were attached to the side seams and drawn tight across the backs of the legs to keep the front of the skirt flat and narrow.

After several years without them, bustles made a fierce comeback during the Late Bustle period (1883-1889). Bustles were larger and higher than before, and it was said that you could place a dinner plate on one. Drapery over these larger bustles became very fanciful, with elaborate layers, pleats, bows and other embellishments, often arranged in an asymmetrical manner. Skirts were still flat at the front, and had less pleated embellishment, which left room for embroidery or other flat designs on the front panels. Necklines were lower for evening events, and sleeve heads had a bit more fullness than before.

Victorian Bustle Dresses

三月 29th, 2016

三月 29th, 2016  ok

ok The skirt bustle is the lesser known but equally beautiful Victorian skirt. When most people think of the Victorian era, they think of the hoop skirt. However, the hoop skirt went out of style in the 1870s, and was replaced with the bustle dress. Although this dress isn’t the definitive style of the Victorian era, it is nonetheless a major contributor to the overall style of the era.

The bustle dress style went through three distinct periods. The first period was the Early Bustle Period, which lasted from 1869-1876. In this period, a separate bodice and skirt were worn, and the bodice was characterized by a high neck and a tight fitting sleeve. The skirt bustle had petticoats underneath it to still give it volume.

The Natural Form Period lasted from 1877-1882, and did away with the bustle completely. However, pleats and draping still gave the effect of a skirt bustle although there was no physical bustle present. Fullness in the skirt was usually drawn to the back so that the silhouette in the front was flat.

The Late Bustle Period appeared in 1883 and lasted until 1889. A true bustle became popular again, and was much more extreme than the previous ones. The bustle skirts were higher and larger than previous bustles, and many times drapery similar to the Natural Form Period was seen.

Edwardian Era

三月 28th, 2016

三月 28th, 2016  ok

ok The Edwardian Era is named for Queen Victoria’s son Edward, who ascended to the throne upon her death in 1901. This was to become an age of unparalleled luxury as the bustles, stiff silks and wools of the 1890’s gave way to the new decorative Art Noveau style. The French termed this period la Belle Epoque (the beautiful era), and the description certainly seems apt as we see the lovely styles that emerged during the years between 1901 and 1914.

As ever, the small waist was admired, but instead of using bustles and elaborate skirt drapery to emphasize the contrast, the new slimmer silhouette featured a bodice that often draped over the waist in front, and all manner of elaborate belts and sashes. Slimmer skirts now skimmed over the hips, and then flared at the hem, giving an inverted lily effect. Blouses became very elaborate in decoration, often featuring embroidery, tucks, and lace inserts all at once. Lighter fabrics, often very fine linen or cotton, were elaborately embroidered and embellished with lace. Softer colors that suited the lighter fabrics became more popular, and white especially was worn for afternoon events, although jewel tones were still admired and often worn. Clothing became so very light that new terms like pneumonia blouse and lingerie dress were coined. Many ladies magazines were published at the time, and several included patterns that could be taken to the local dressmaker, or if the lady was talented, could be made at home. New styles were always touted as coming from France, as this was considered the leading fashion center of the day.

Of course, all this lightweight clothing would never do for a New England winter, and warmer garments had to be worn. The Edwardian era saw the rise of the suit as a fashionable garment for ladies. Perhaps the greatest proponent of this new style of dress – thought mannish by some – was the “Gibson Girl”, who emerged athletic and independent, from the cocoon of gauze and lace of a few years earlier.

No discussion of this era would be complete without mention of the signature accessories of the day. Don’t we all love those incredible Edwardian hats? As the overall silhouette became slimmer, hats (and the hairdos under them) became increasingly larger and wider. Feathers were used extensively; to the point that certain species of birds were hunted to near extinction, and the first-ever laws were passed to protect them. The “picture hat” was a must-have accessory for any lady venturing out of her home. Gloves were worn at all times in public, often of washable leather, but for special events they would be made of suede or lace. A parasol was often carried, and in the summer this accessory also dripped with ribbons and lace, adding to the overall frilly, feminine effect of the outfit.

cane or brass hoops. Furthermore, the flattened steel wire was so elastic and strong that it could be severely bent (going through doorways or sitting), and yet the skirt would spring back to its original shape. The cage crinoline was adopted with enthusiasm; it was light and only required one or two petticoats worn over the top to prevent the steel bands from appearing as ridges in the skirt. At its peak in size, the crinoline reached a diameter of up to 180 centimeters, almost six feet. The wearing of the crinoline was a fashion that was adopted by all classes, and worn by both women and young girls.

cane or brass hoops. Furthermore, the flattened steel wire was so elastic and strong that it could be severely bent (going through doorways or sitting), and yet the skirt would spring back to its original shape. The cage crinoline was adopted with enthusiasm; it was light and only required one or two petticoats worn over the top to prevent the steel bands from appearing as ridges in the skirt. At its peak in size, the crinoline reached a diameter of up to 180 centimeters, almost six feet. The wearing of the crinoline was a fashion that was adopted by all classes, and worn by both women and young girls.