Gothic Black and Red Euro Court Dress & Witch Halloween Costume

Condition: Brand New

Shown Color: Black and Red

Sleeves: Long Sleeves

Length: Floor Length

Material: Velvet, Silk-like

Specific: Ruffle

Occasion: Versatile

Includes: Dress, Overcoat, Hoopskirt

This is featured post 1 title

To set your featured posts, please go to your theme options page in wp-admin. You can also disable featured posts slideshow if you don't wish to display them.

This is featured post 2 title

To set your featured posts, please go to your theme options page in wp-admin. You can also disable featured posts slideshow if you don't wish to display them.

This is featured post 3 title

To set your featured posts, please go to your theme options page in wp-admin. You can also disable featured posts slideshow if you don't wish to display them.

Black and Red Euro Court Dress & Witch Halloween Costume

十月 3rd, 2015

十月 3rd, 2015  ok

ok Georgian Period Dress Marie Antoinette Long Stain Masquerade Ball Gown

十月 2nd, 2015

十月 2nd, 2015  ok

ok Georgian Period Dress Marie Antoinette Long Stain Masquerade Ball Gown

Condition: Brand New

Shown Color: Refer to Image

Sleeves: Long Sleeves

Length: Floor Length

Material: Satin, Brocade

Occasion: Versatile

Include: Dress

Georgian Period Dress Marie Antoinette Stain Masquerade Ball Gown Party Dresses

十月 2nd, 2015

十月 2nd, 2015  ok

ok Georgian Period Dress Marie Antoinette Stain Masquerade Ball Gown Party Dresses

Condition: Brand New

Shown Color: Refer to Image

Sleeves: Long Sleeves

Length: Floor Length

Material: Satin, Brocade

Occasion: Versatile

Include: Dress

Georgian Victorian Gothic Period Dress Masquerade Ball Gown Reenactment Dresses

十月 1st, 2015

十月 1st, 2015  ok

ok Georgian Victorian Gothic Period Dress Masquerade Ball Gown Reenactment Dresses

Condition: Brand New

Shown Color: Refer to Image

Sleeves: Long Sleeves

Length: Floor Length

Material: Satin, Brocade

Occasion: Versatile

Include: Dress

18th Century Period Dress PLUM Marie Antoinette Gown Reenactment Theater Clothing

九月 29th, 2015

九月 29th, 2015  ok

ok 18th Century Period Dress PLUM Marie Antoinette Gown Reenactment Theater Clothing

Condition: Brand New

Shown Color: Plum

Sleeves: Long Sleeves

Length: Floor Length

Material: Brocade + Satin

Specific: Bows

Occasion: Versatile

Include: Dress

18th Century Marie Antoinette Purple Victorian Dress Prom

九月 29th, 2015

九月 29th, 2015  ok

ok 18th Century Marie Antoinette Victorian Dress Prom

Condition: Brand New

Material: Brocade, Satin

Sleeves: Long Sleeves

Length: Floor Length

Occasion: Versatile

Include: Dress

History of Costume Rococo florid or excessively elaborate

八月 13th, 2015

八月 13th, 2015  ok

ok A significant shift in culture occurred in France and elsewhere at the beginning of the 18th century, known as the Enlightenment, which valued reason over authority. In France, the sphere of influence for art, culture and fashion shifted from Versailles to Paris, where the educated bourgeoisie class gained influence and power in salons and cafés. The new fashions introduced therefore had a greater impact on society, affecting not only royalty and aristocrats, but also middle and even lower classes. Ironically, the single most important figure to establish Rococo fashions was Louis XV’s mistress Madame Pompadour. She adored pastel colors and the light, happy style which came to be known as Rococo, and subsequently light stripe and floral patterns became popular. Towards the end of the period, Marie Antoinette became the leader of French fashion, as did her dressmaker Rose Bertin. Extreme extravagance was her trademark, which ended up majorly fanning the flames of the French Revolution.

Fashion designers gained even more influence during this era, as people scrambled to be clothed in the latest styles. Fashion magazines emerged during this era, originally aimed at intelligent readers, but quickly capturing the attention of lower classes with their colorful illustrations and up-to-date fashion news. Even though the fashion industry was ruined temporarily in France during the Revolution, it flourished in other European countries, especially England.

Fashion designers gained even more influence during this era, as people scrambled to be clothed in the latest styles. Fashion magazines emerged during this era, originally aimed at intelligent readers, but quickly capturing the attention of lower classes with their colorful illustrations and up-to-date fashion news. Even though the fashion industry was ruined temporarily in France during the Revolution, it flourished in other European countries, especially England.

During this period, a new silhouette for women was developing. Panniers, or wide hoops worn under the skirt that extended sideways, became a staple. Extremely wide panniers were worn to formal occasions, while smaller ones were worn in everyday settings. Waists were tightly constricted by corsets, provided contrasts to the wide skirts. Plunging necklines also became common. Skirts usually opened at the front, displaying an underskirt or petticoat. Pagoda sleeves arose about halfway through the 18th century, which were tight from shoulder to elbow and ended with flared lace and ribbons. There were a few main types of dresses worn during this period. The Watteau gown had a loose back which became part of the full skirt and a tight bodice. The robe à la française a lso had a tight bodice with a low-cut square neckline, usually with large ribbon bows down the front, wide panniers, and was lavishly trimmed with all manner of lace, ribbon, and flowers. The robe à l’anglais featured a snug bodice with a full skirt worn without panniers, usually cut a bit longer in the back to form a small train, and often some type of lace kerchief was worn around the neckline. These gowns were often worn with short, wide-lapeled jackets modeled after men’s redingotes. Marie Antoinette introduced the chemise à la reine (pictured right), a loose white gown with a colorful silk sash around the waist. This was considered shocking for women at first, as no corset was worn and the natural figure was apparent. However, women seized upon this style, using it as a symbol of their increased liberation.

lso had a tight bodice with a low-cut square neckline, usually with large ribbon bows down the front, wide panniers, and was lavishly trimmed with all manner of lace, ribbon, and flowers. The robe à l’anglais featured a snug bodice with a full skirt worn without panniers, usually cut a bit longer in the back to form a small train, and often some type of lace kerchief was worn around the neckline. These gowns were often worn with short, wide-lapeled jackets modeled after men’s redingotes. Marie Antoinette introduced the chemise à la reine (pictured right), a loose white gown with a colorful silk sash around the waist. This was considered shocking for women at first, as no corset was worn and the natural figure was apparent. However, women seized upon this style, using it as a symbol of their increased liberation.

Women’s heels became much daintier with slimmer heels and pretty decorations. At the beginning of the period, women wore their hair tight to the head, sometimes powdered or topped with lace kerchiefs, a stark contrast to their wide panniers. However, hair progressively was worn higher and higher until wigs were required. These towering tresses were elaborately curled and adorned with feathers, flowers, miniature sculptures and figures. Hair was powdered with wheat meal and flour, which caused outrage among lower classes as the price of bread became dangerously high.

Men generally wore different variations of the habit à la française: a coat, waistcoat, and breeches. The waistcoat was the most decorative piece, usually lavishly embroidered or displaying patterned fabrics. Lace jabots were still worn tied around the neck. Breeches usually stopped at the knee, with white stockings worn underneath and heeled shoes, which usually had large square buckles. Coats were worn closer to the body and were not as skirt-like as during the Baroque era. They were also worn more open to showcase the elaborate waistcoats. Tricorne hats became popular during this period, often edged with braid and decorated with ostrich feathers. Wigs were usually worn by men, preferably white. The cadogan style of men’s hair developed and became popular during th

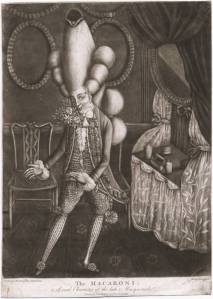

Men generally wore different variations of the habit à la française: a coat, waistcoat, and breeches. The waistcoat was the most decorative piece, usually lavishly embroidered or displaying patterned fabrics. Lace jabots were still worn tied around the neck. Breeches usually stopped at the knee, with white stockings worn underneath and heeled shoes, which usually had large square buckles. Coats were worn closer to the body and were not as skirt-like as during the Baroque era. They were also worn more open to showcase the elaborate waistcoats. Tricorne hats became popular during this period, often edged with braid and decorated with ostrich feathers. Wigs were usually worn by men, preferably white. The cadogan style of men’s hair developed and became popular during th e period, with horizontal rolls of hair over the ears. French elites and aristocrats wore particularly lavish clothing and were often referred to as “Macaronis,” as pictured in the caricature on the right. The lower class loathed their open show of wealth when they themselves dressed in little more than rags.

e period, with horizontal rolls of hair over the ears. French elites and aristocrats wore particularly lavish clothing and were often referred to as “Macaronis,” as pictured in the caricature on the right. The lower class loathed their open show of wealth when they themselves dressed in little more than rags.

Fashion played a large role in the French Revolution. Revolutionaries characterized themselves by patriotically wearing the tricolor—red, white, and blue—on rosettes, skirts, breeches, etc. Since most of the rebellion was accomplished by the lower class, they called themselves sans-culottes, or “without breeches,” as they wore ankle-length trousers of the working class. This caused knee breeches to become extremely unpopular and even dangerous to wear in France. Clothing became a matter of life or death; riots and murders could be caused simply because someone was not wearing a tricolor rosette and people wearing extravagant gowns or suits were accused of being aristocrats.

The Rococo era was defined by seemingly contrasting aspects: extravagance and a quest for simplicity, light colors and heavy materials, aristocrats and the bourgeoisie. This culmination produced a very diverse era in fashion like none ever before. Although this movement was largely ended with the French Revolution, its ideas and main aspects strongly affected future fashions for decades.

WHOLESALELOLITA.COM, Ladies and their Fans-The Victorian Era-Victorian Days

八月 13th, 2015

八月 13th, 2015  ok

ok “In the days when women yet blushed, in the days when they desired to dissimulate this embarrassment and timidity, large fans were the fashion; they were at once both a countenance and a veil. Flirting their fans, women concealed their faces; now they blush little, fear not at all, have no care to hide themselves, and carry in consequence imperceptible fans.” …*Madame de Genlis

Carrying in left hand, open: “Come and talk to me”

Twirling it in the left hand: “We are watched”

Twirling in the right hand: “I love another”

Drawing across the cheek: “I love you”

Presented shut: “Do you love me?”

Drawing across the eyes: “I am sorry”

Letting it rest on right cheek: “Yes”

Letting it rest on left cheek: “No”

Open and shut: “You are cruel”

Dropping it: “We will be friends”

Fanning slowly: “I am married”

Fanning quickly: “I am engaged”

With handle to lips: “Kiss me”

Open wide: “Wait for me”

Carrying in right hand in front of face: “Follow me”

Placing it on left ear: “I wish to get rid of you”

Carrying it in the right hand: “You are too willing”

Drawing through the hand: “I hate you”

Placed behind head: “Don’t forget me”

With little finger extended: “Good-bye”

Quickly fanning herself: “I love you so much”

Looking closely at the painting: “I like you”

Drawing it across the forehead: “You have changed”

Resting the fan on her lips: “I don’t trust you”

Touching tip with finger: “I wish to speak with you”

Hitting her hand’s palm: “Love me”

Hitting any object: “I’m impatient”

Hiding the sunlight: “You’re ugly”

The shut fan held to the heart: “You have won my love”

Carrying in left hand in front of face: “Desirous of acquaintance”

Presenting a number of sticks, fan part opened: “At what hour?”

Threaten with the shut fan: “Do not be so imprudent”

Gazing pensively at the shut fan: “Why do you misunderstand me?”

Pressing the half-opened fan to the lips: “You may kiss me”

Clasping the hands under the open fan: “Forgive me I pray you”

Cover the left ear with the open fan: “Do not betray out secret”

Shut the fully opened fan very slowly: “I promise to marry you”

The lady appears at the balcony, slowly fanning her face, then she shuts the balcony: “I can’t go out”

If she does it excitedly, leaving the balcony open: “I’ll go out soon”

Touching the unfolded fan in the act of waving: “I long always to be near thee”

The shut fan resting on the right eye: “When may I be allowed to see you?”

Fanning herself with her left hand: “Don’t flirt with that woman”

Running her fingers through the fan’s ribs: “I want to talk to you”

Slowly fanning herself: “Don’t waste your time, I don’t care about you”

Moving her hair away from her forehead: “Don’t forget me”

Passing the fan from hand to hand: “I see that you are looking at another woman”

Carrying the fan closed and hanging from her left hand: “I’m engaged”

Carrying the fan closed and hanging from her right hand: “I want to be engaged”

Quickly and impetuously closing the fan: “I’m jealous”

Resting the fan on her heart: “My love for you is breaking my heart”

Half-opening the fan over her face: “We are being watched over”

Fans were known to the ancients, and kept the flies off Pharaoh. The Japanese, clever as always, devised the folding variety, and they became enormously popular in the Western world. Whether the thing was made of feathers, silk, or paper, the idea at first was simply to cool the person. But there was something exquisitely graceful about a beautiful lady waving her fan and, as women will, they discovered it. It was a new way to say yes, no, or maybe.

The origin of hand fans can be traced as far back as four thousand years ago in Egypt. The fan was seen as a sacred instrument, used in religious ceremonies, and as a symbol of royalty power. With the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, two elaborate fans were found in his tomb, one with a golden handle covered in ostrich feathers and the other was ebony, covered with gold and precious stones. Three thousand year old drawings still exist showing elegant Chinese ladies using fans. The ancient Greeks wrote poems of fans being the “scepters of feminine beauty” and Romans brought Greek fans back to Rome as objects of great value. Images of punk ha wallahs waving enormous branches from palm trees over the Kings and Queens of ancient civilizations also indicate the early pomp and glory of fans.

The origin of hand fans can be traced as far back as four thousand years ago in Egypt. The fan was seen as a sacred instrument, used in religious ceremonies, and as a symbol of royalty power. With the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, two elaborate fans were found in his tomb, one with a golden handle covered in ostrich feathers and the other was ebony, covered with gold and precious stones. Three thousand year old drawings still exist showing elegant Chinese ladies using fans. The ancient Greeks wrote poems of fans being the “scepters of feminine beauty” and Romans brought Greek fans back to Rome as objects of great value. Images of punk ha wallahs waving enormous branches from palm trees over the Kings and Queens of ancient civilizations also indicate the early pomp and glory of fans.

In the seventeenth century, China was importing huge quantities of exotic fans into Europe. These small utilitarian instruments could regulate ambient air temperature and provide a means of self-cooling or hide one’s temper and blushes. In addition, fans could shield the eyes from the glare of the sun, prevent an unfashionable tanning of the skin outdoors and prevent ruddy complexions arising from too vigorous a fire indoors, hence, the development of the hand-held fire screen. The eighteenth century Georgian fans represented the most exquisite objects d’art, the perfect gift for a lady of good taste, and connoisseur of the handcrafted object. Fans also had a particular place in the masquerade balls across Europe in that century, hiding the faces of their owners, as part of an elaborate ritual of flirtation.

Fan languages or “fan flirtation rules” were a way to cope with the restricting social etiquette. The main rules must have been practiced just to remember them, not to mention the young fellows who also had to learn the language of fans!

Holding a fan in the left hand signified “desired acquaintance”

Resting the fan on the right cheek meant “yes” and left cheek “no”

Twirling a fan in the left hand meant “I wish to be rid of you”

and the right hand meant “I love another”

A fan held on the left ear signified “you have changed”

Pulling a fan across the forehead meant “we are watched”,

across the eyes meant “I am sorry”

A wide open fan meant “wait for me”

Dropping a fan meant “we could be friends”

Fast fanning meant “I am married”

Swift pulling of a fan through the hand meant “I hate you”

Placing the handle of a fan to the lips meant “kiss me”

By 1865 the fan was an indispensable fashion accessory for the emergent middle classes, reaching the peak of its success in the Victorian era. Fashion dictated that all women have a fan. Like many other utilitarian objects for women, fans became works of art. The kind of fan a woman owned was based on her social status, ranging from street vendors to hand painted, mother of pearl or ivory inlaid with gold and precious jewels. This availability to all, led to an extraordinary snobbery about the fan.

Fans survived into the twentieth century but much of the past elegance, and the unspoken language of oriental mystique had fallen to the side, except in the case of postcards. Fans made one last appearance during the postcard era and then, once again, they became practical as souvenirs, advertisements (including political), decorations and friendship gifts.

A History of the Fan

A fan can be functional, used in ceremonies, a fashion statement or a means for advertising. A type of fan was used in ancient Roman, Greek, Egyptian and Chinese cultures. Some of the earliest examples include two fans discovered in Tutankhamen’s tomb when it was excavated in 1922. These early fans were single shapes fixed to a handle. The first European country to produce fans was Italy in about 1500. This was in Venice and was a result of the city being a major trading centre for the Orient to the rest of Europe.

As trade increased during the 16th century fans grew in popularity as a fashionable commodity. In the 17th century The Guild of Fan Makers was established thus acknowledging its professional status. A century later the Worshipful Company of Fan Makers formed in 1709. Until the mid 17th century fans continued to be very much a luxury item, often made from some of the most expensive materials and jewels. By the latter part of the 17th century the range of fans was increasing and France overtook Italy as the main centre for fan production. By the 18th century most countries were making fans of some kind and fan painting had become a recognised craft. Fans were now an essential fashion accessory and styles echoed other trends in fashionable dress. A decline in fan use began in the early 20th century and they became more of an advertising tool rather than a fashion accessory. However, their popularity continues in Spain, where they became part of the Spanish culture, and in hot climates for keeping cool.

Throughout their history fans have been made from a diverse range of materials. Some of the earliest Egyptian and Chinese fans were made of feathers. The peacock feather was popular because of its eye motif which was seen as a protective symbol. Colourful feathers were used for fans in the third quarter of the 19th century. During the latter part of the 19th century the neutral tones of ostrich feathers mounted on mother of pearl, ivory or tortoiseshell echoed the softer tones of their contemporary dress. 1920s fashions demanded a single ostrich plume dyed to match dress colours. Leaves of folding fans have been made of fine animal skins (including that of unborn lambs and often referred to as ‘chicken skin’), vellum, paper, lace, silk and other textiles. Vellum and ‘chicken skin’ were used mainly during the 16th and 17th centuries after which paper increased in popularity. These leaves were painted, the first printed fan dates to the 1720s. Tortoiseshell, ivory, bone, mother of pearl, metal and wood have all been used as guards and sticks. All either highly decorative: jewelled, carved, pierced, gilded, lacquered, painted, printed or simply left plain. Artificial materials have been used too. Celluloid, one of the earliest plastics was being used to imitate tortoiseshell during the late 19th century.

Styles

The most common styles of fan are folding, bris?, cockade or a simple rigid shape on a handle. A folding fan is made from a set of sticks with a pleated leaf. The two outer sticks are described as guards and they are frequently decorated. The guards and sticks are held together at the base with a rivet. Bris? fans are made from separate sticks which are linked together at the top with ribbon and the base is fixed in the same way as a folding fan. Cockade fans have a folding leaf which is designed to open into a full circle and it closes into a single guard. Decorative styles vary according to country of origin and changing taste in dress. Painted scenes, landscapes and vignettes inspired by religious and mythological subject matter ran parallel to contemporary developments in the fine and decorative arts, particularly during the 17th and 18th centuries. These earlier styles were revived again in the 19th century. Other influences include historical and cultural events. The excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii in Italy during the 18th century encouraged a fascination with classical motifs. Wealthy young men travelled to see the sites and souvenir fans were available for them to purchase for their female relatives. The French Revolution provided a source for printed fans, sometimes produced to make a political statement.

Communication

From the sixteenth century onwards the fan was used in fashionable society as a means of communication. The messages conveyed on the whole were those of love. This form of sign language was published in contemporary etiquette books and magazines. The Original Fanology or Ladies’ Conversation Fan which had been created by Charles Francis Badini, was published by William Cock in London in 1797. It contained details on how to hold complete conversations through simple movements of a fan. Both men and women carried fans and understood the different messages. Some of the most common are listed below.

Placing your fan near your heart = I love you

Letting the fan rest on the right cheek = Yes

Letting the fan rest on the left cheek = No

Dropping the fan = We will be friends

Fanning slowly = I am married

Fanning quickly = I am engaged

Drawing the fan across the eyes = I am sorry

To open a fan wide = Wait for me

A half closed fan pressed to the lips = You may kiss me

Twirling the fan in the right hand = I love another

Twirling the fan in the left hand = We are being watched

Shutting a fully open fan slowly = I promise to marry you

A closed fan resting on the right eye = When can I see you

Carrying a open fan in the left hand = come and talk to me

Touching the tip of the fan with a finger = I wish to speak to you

Copyright Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum

*[Madame de Genlis, French writer and educator (1746 – 1830), one of the most popular, prolific authors of her day]

Afternoon Dress WHOLESALELOLITA.COM

八月 12th, 2015

八月 12th, 2015  ok

ok Afternoon dress

Charles Frederick Worth was born in England and spent his young adulthood working for textile merchants in London while researching art history at museums. In 1845 he moved to Paris and worked as a salesman and a dressmaker before partnering with Otto Bobergh to open the dressmaking shop, Worth and Bobergh, in 1858. They were soon recognized by royalty and major success followed. In 1870 Worth became the sole proprietor of the business. At his shop, Worth fashioned completed creations which he then showed to clients on live models. Clients could then order their favorites according to their own specifications. This method is the origin of haute couture. Worth designed gowns which were works of art that implemented a perfect play of colors and textures created by meticulously chosen textiles and trims. The sheer volume of the textiles he employed on each dress is testimony to his respect and support of the textile industry. Worth’s creative output maintained its standard and popularity throughout his life. The business continued under the direction of his sons, grandsons and great-grandsons through the first half of the twentieth century.